Imagine that some two decades before Thomas Edison (widely regarded as the “inventor of recorded sound”) you had created a system for recording sounds, music and the human voice. Well, this is exactly what happened to Parisian printer and experimenter Edouard-Léon Scott de Martinville, who devised such a system in 1857.

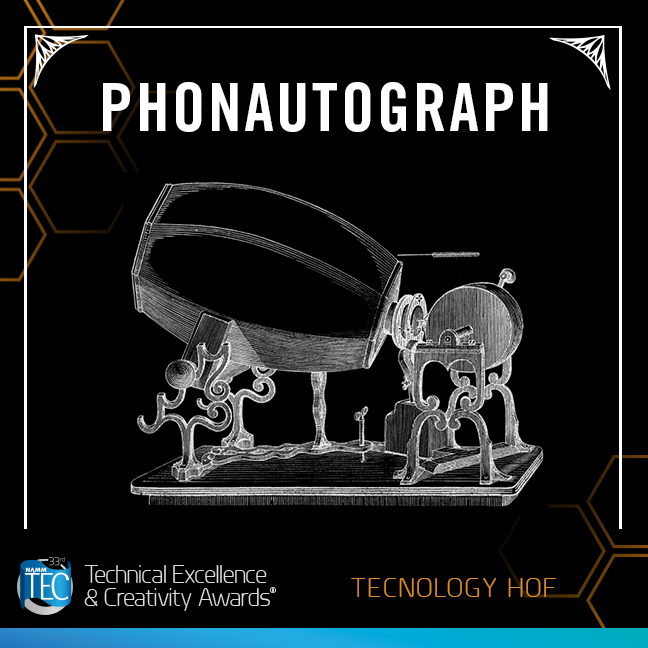

The device, which he called the phonoautograph, used acoustic transducers that were similar to the recording/playback horns used by Edison and fellow audio pioneer Emile Berliner in their phonograph and gramophone systems). The narrow end of Scott de Martinville’s phonoautograph horn ended in a flexible diaphragm that reacted to sound waves, and vibrated an attached bristle or fine feather quill in response to the audio. To capture the audio output in a visible form, a sheet of paper covered with a thin layer of smoke particles rotated against the feather tip, with the result being a “drawing’ of the waveform. Once on paper, these “phonautograms” could be transferred onto photographic plates to create a permanent versions for later study of the wave motion.

And there’s the rub — Scott de Martinville was mainly interested in creating a tool for studying visual analogies of various sound waves, and had no interest in creating an audio playback system.

Over the ensuing years, he continued to improve the phonautograph devices, and collected numerous “recordings” of various sources — natural sounds, spoken voices, singing and more. Unfortunately, with no means of playing back the phonautograms, and Scott de Martinville’s work remained a interesting novelty — a mere footnote in the history of recorded audio.

Flash forward 150 years into the future and a group of early-21st century researchers from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratories (Berkeley, California) wondered whether digital technology could unlock the hidden sounds from these captured waveforms. After some tweaking of some high-resolution scans of the printed waveforms — many of which had been locked away for decades — sounds from long ago began to emerge.

One phonautogram of particular interest was a voice singing part of “Au Clair de La Lune,” but not knowing the pitch (recording speed) of the original, there was no way of telling whether the performance was a child, man or woman. As luck would have it, another phonautogram happened to be a capture of a tuning fork, and from there, determining the correct pitch of the other recordings was a simple affair. As it turns out, the crude “Au Clair de La Lune,” recording was performed by a male voice — presumably Scott de Martinville himself. And so the mystery of the 150+ year-old phonoautograms was finally solved.